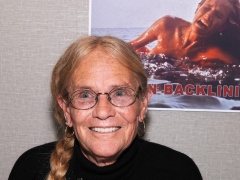

Singer, actor, producer and activist Harry Belafonte, who spawned a calypso craze in the U.S. with his music and blazed new trails for African American performers, died Tuesday of congestive heart failure at his Manhattan home. He was 96.

An award-winning Broadway performer and a versatile recording and concert star of the ’50s, the lithe, handsome Belafonte became one of the first Black leading men in Hollywood. He later branched into production work on theatrical films and telepics.

As his career stretched into the new millennium, his commitment to social causes never took a back seat to his professional work.

An intimate of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Belafonte was an important voice in the ’60s civil rights movement, and he later embarked on charitable activities on behalf of underdeveloped African nations. He was an outspoken opponent of South Africa’s apartheid policies.

Among the most honored performers of his era, Belafonte won two Grammy Awards (and the Recording Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000), a Tony and an Emmy. He also received the Motion Picture Academy’s Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the Governors Awards ceremony in 2014.

Harold George Belafonte Jr. was born in New York but was sent to live with his grandmother in Jamaica at age 5, returning to attend high school in New York. But Jamaica’s indigenous calypso and mento would supply crucial material for his early musical repertoire.

After serving in the war, Belafonte gravitated to the New York theatrical scene. An early mentor was the famed Black actor, singer and activist Paul Robeson. He studied acting with Erwin Piscator and attended Broadway shows — on a single ticket he would hand off at intermission — with another struggling young actor, Sidney Poitier. Like Poitier, he performed at Harlem’s American Negro Theater.

Belafonte first made his mark, however, as a nightclub singer. Initially working in a pop and jazz vein, Belafonte began his singing career at New York’s Royal Roost and made his recording debut in 1949 on Roost Records. He soon developed a growing interest in American folk music.

A national tour and dates at New York’s Village Vanguard and Blue Angel followed. A scout for MGM spotted him at the latter venue and, following a screen test, Belafonte secured a role opposite Dorothy Dandridge in “Bright Road” (1953).

The same year, Belafonte made his Rialto debut in the revue “John Murray Anderson’s Almanac,” for which he received the Tony for best performance by a featured actor in a musical.

Ironically, while Belafonte was cast as a lead in Otto Preminger’s 1954 musical “Carmen Jones” — based on Oscar Hammerstein II’s Broadway adaptation of Bizet’s opera “Carmen” — his singing voice was dubbed by opera singer LeVern Hutcherson. Belafonte would soon explode in his own right as a pop singer.

He made his RCA Records debut in 1954 with “Mark Twain and Other Folk Favorites”; he had performed the titular folk song with his guitarist Millard Thomas in his Tony-winning Broadway turn. The 1956 LP “Belafonte,” featuring a similar folk repertoire, spent six weeks at No. 1.

Those collections were a mere warm-up to “Calypso.” The 1956 album sparked a nationwide calypso craze, spent a staggering 31 weeks at No. 1 and remains one of the four longest-running chart-toppers in history. It spawned Belafonte’s signature hit, “Banana Boat Song (Day-O),” which topped the singles chart for five weeks. A parody of that ubiquitous number by Stan Freberg reached No. 25 in 1957. Director Tim Burton employed the tune to bright effect in his 1988 comedy “Beetlejuice.”

Belafonte would cut five more top-five albums — including two live sets recorded at Carnegie Hall — through 1961. His 1960 collection “Swing Dat Hammer” received a Grammy as best ethnic or traditional folk album; he scored the same award for 1965’s “An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba,” a collaboration with South African folk artist Miriam Makeba.

He also supplied early employment for a future folk icon: His 1962 album “Midnight Special” featured harmonica work by Bob Dylan.

A frequent guest on TV variety shows, Belafonte became the first Black performer to garner an Emmy with his 1959 special “Tonight With Belafonte.”

Belafonte made his first steps into film production with two features he toplined: end-of-the-world drama “The World, the Flesh, and the Devil” (1959) and the heist picture “Odds Against Tomorrow” (1960). However, discontent with the roles he was being offered, he would remain absent from the big screen for the remainder of the ’60s and busied himself with recording and international touring as his involvement in the civil rights movement deepened.

Closely associated with clergyman-activist King, Belafonte provided financial support to the civil rights leader and his family. He also funded the Freedom Riders and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and was a key figure in the organization of the historic March on Washington of August 1963.

The racial tumult of the ’60s hit close to home: In 1968 he became the center of a furor when he appeared as a guest star on an NBC special hosted by British pop singer Petula Clark. During a performance of an anti-war ballad, Clark clutched Belafonte’s arm. Doyle Lott, VP for sponsor Chrysler-Plymouth, was present at the taping and demanded the number be excised, saying the “interracial touching” might offend Southern viewers. But Clark, who owned the show, put her foot down and the show aired as recorded, while exec Lott was fired by the automaker.

Belafonte returned to feature films in 1970 in the whimsical “The Angel Levine” alongside Zero Mostel. He co-starred with old friend Poitier in the comedies “Buck and the Preacher” (1972) and “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974), both directed by Poitier.

His acting appearances would be sporadic for the remainder of his career. Notably, he appeared opposite John Travolta in “White Man’s Burden” (1995), an alternate-universe fantasy-drama about racism; Robert Altman’s ensemble period drama “Kansas City” (1996); and “Bobby” (2006), Emilio Estevez’s account of Sen. Robert Kennedy’s 1968 assassination.

In 1985, Belafonte’s activism and musicianship intertwined when he helped organize the recording session for “We Are the World,” the all-star benefit single devoted to alleviating African famine. His appearance on that huge hit led to “Paradise in Gazankulu” (1988), his first studio recording in more than 10 years.

His latter-day production work included the 1984 hip-hop drama “Beat Street” and the 2000 miniseries “Parting the Waters,” based on historian Taylor Branch’s biography of Martin Luther King Jr.

In 2002, “The Long Road to Freedom: An Anthology of Black Music,” an immense collection of African and African-American music recorded and compiled by Belafonte over the course of a decade and originally set for release by RCA in the ’70s, was finally released as a five-CD set on Universal’s Buddha imprint. It garnered three Grammy nominations.

In later years, Belafonte remained as outspoken as ever, and his views sometimes courted controversy. He was a foe of South African apartheid, opposed the U.S.’s Cuban embargo and denounced George W. Bush’s military incursion into Iraq.

Belafonte was the son of a Jamaican housekeeper and a Martiniquan chef, spending the early and late parts of his childhood in Harlem but the crucial middle period in Jamaica. He enlisted in the Navy in 1944; during his service, he encountered the writing of W.E.B. DuBois, co-founder of the NAACP and a key influence.

He was accorded the Kennedy Center Honor in 1989 and the National Medal of the Arts in 1994.

Belafonte published his memoir “My Song,” written with Michael Shnayerson, in 2011. Susanne Rostock’s biographical documentary “Sing Your Song” was released in early 2012.

He is survived by his third wife Pamela; daughters Shari, Adrienne and Gina; son David; stepchildren Sarah and Lindsey; and eight grandchildren.