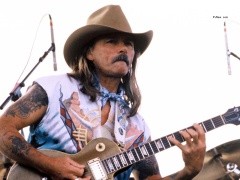

Dickey Betts, whose country-inflected songwriting and blazing, lyrical guitar work opposite Duane Allman in the Allman Brothers Band helped define the Southern rock genre of the ‘60s and ‘70s, died Thursday in Osprey, Fla. He was 80.

His family posted a statement on Instagram, writing, “It is with profound sadness and heavy hearts that the Betts family announce the peaceful passing of Forrest Richard ‘Dickey’ Betts (December 12, 1943 – April 18, 2024) at the age of 80 years old. The legendary performer, songwriter, bandleader and family patriarch passed away earlier today at his home in Osprey, FL., surrounded by his family. Dickey was larger than life, and his loss will be felt world-wide.”

In 1969, Betts and bassist Berry Oakley of the Florida band the Second Coming joined members of two other Sunshine State groups — guitarist Duane Allman and his keyboard-playing brother Gregg of the Hour Glass and drummer Butch Trucks of the 31st of February – and Mississippi-born drummer Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson in a new unit that ultimately based itself in Macon, Ga.

Riding a powerful twin-guitar sound that fused rock, blues and country, the Allman Brothers Band inspired a host of like-minded groups throughout the South, many of which would find a home at Capricorn Records, the custom imprint established by the Allmans’ manager Phil Walden.

A potent live act noted for their jamming abilities (on such numbers as Betts’ instrumental “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed”), the Allmans made their major commercial breakthrough in 1971 with the No. 13 two-LP concert set “At Fillmore East.”

Duane Allman’s tragic death at 24 in an October 1971 motorcycle accident in Macon thrust Betts into a more prominent role in the group as songwriter, instrumentalist and sometime lead vocalist.

He contributed the band’s long-running concert staple “Blue Sky” to 1972’s “Eat a Peach,” the group’s first album without Duane, which soared to No. 4. The 1973 release “Brothers and Sisters” rose to No. 1 nationally on the back of the countrified Betts-penned single “Ramblin’ Man,” which peaked at No. 2.

The guitarist went on to write the Allman’s No. 29 single “Crazy Love” (1979) and co-authored the act’s last top-40 single, “Straight From the Heart” (No. 39, 1981).

Betts’ service with the Allman Brothers Band – which over time would come to include guitarists Dan Toler and Warren Haynes, both members of his solo outfits – proved to be long, discontinuous and frequently tumultuous.

While the group was one of the biggest touring attractions of the day, the escalating drug use and tempestuous interpersonal relationships of its personnel led to a split in 1976, in the wake of their No. 5 album “Win, Lose or Draw.” They regrouped three years later and issued their last top-10 album, “Enlightened Rogues.”

Though the Allmans remained a consistent live draw through the ‘80s and ‘90s despite waning album sales, ongoing conflict between Betts and Gregg Allman came to a head in 2000, when the guitarist made a precipitous exit, under fire from his band mates, from the group he had co-founded 31 years earlier. His onetime sideman Haynes remained with the group until it disbanded for good in 2014.

Both during and after his tenure with the Allmans, Betts sustained a solo career, often under the group handle Great Southern. His most popular solo work was his first LP “Highway Call,” which reached No. 19 in 1974, at the height of the Allmans’ popularity.

Rock journalist-turned-filmmaker Cameron Crowe said he based the character played by Billy Crudup in his rock-themed 2000 film “Almost Famous” on Betts.

“Crudup’s look, and much more, is a tribute to Dickey,” Crowe told Rolling Stone in 2017. “Dickey seemed like a quiet guy with a huge amount of soul, possible danger and playful recklessness behind his eyes. He was a huge presence.”

Betts was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of the Allman Brothers Band in 1995.

He was born Forrest Richard Betts in West Palm Beach, FL, on Dec. 12, 1943. (He was variously billed professionally as “Dick,” “Dicky” or “Richard” before settling on “Dickey” in the mid-‘70s.) His father and uncles all played music, and he picked up the ukulele at the age of five before graduating to his brother’s guitar. Reared on the Grand Ole Opry’s weekly radio performances, he began gravitating to the blues after hearing local guitarist Jimmy Paramore and became active in a number of regional Florida bands.

Betts’ act the Soul Children became known as the Blues Messengers, and finally the Second Coming, with the addition of bassist Oakley, a Chicago native who had become a fixture on the Sarasota music scene. A fateful meeting with the Allman siblings at a Jacksonville club where the Hour Glass was playing ultimately led the finalization of the six-man Allman Brothers Band lineup in March 1969.

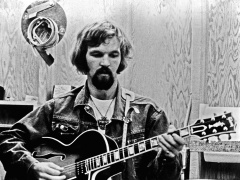

The group’s first two albums, its self-titled 1969 debut and 1970’s “Idlewild South,” were not enormous successes, but ex-session star Duane Allman’s growing rep as a musician’s musician and his fiery interplay with Betts turned the act into a formidable attraction at rock ballrooms and festivals.

Its original incarnation had its apotheosis on “At Fillmore East,” recorded live at Bill Graham’s New York venue in March 1971. Featuring a searing 13-minute rendition of Betts’ “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” (which took its name from a tombstone the guitarist spotted in a Macon cemetery), the set was ultimately certified for sales of 1 million units.

Duane Allman’s sudden death just six months after the live album’s release left the band’s future briefly in doubt, but the surviving members unanimously decided to carry on as a five-piece, with Betts initially taking on de facto leadership.

Just three months after the release of its massive hit “Brothers and Sisters” – which included “Ramblin’ Man” and the memorable Betts instrumental “Jessica,” named after the guitarist’s daughter — bassist Oakley was killed in a motorcycle crash in Macon, just blocks from the site of the accident that took Duane Allman’s life.

While the Allman Brothers Band soldiered on with the surviving original members and a shifting cast of additional personnel, Betts began to split his time with his side projects Great Southern and the Dickey Betts Band, which released three studio albums between 1977-88.

Gregg Allman’s testimony against the Allman Brothers Band’s security man Scooter Herring in a federal drug case led to the rupture of the group in 1976, with Betts declaring in Rolling Stone, “There is no way we can work with Gregg again. Ever.”

However, the band reunited for recording and touring in 1979 (following an initial reconciliation at a Great Southern show in New York’s Central Park) and – after another hiatus and a 1986 joint tour by Allman and Betts — again in 1989, with Betts appearing on six studio albums and three official live recordings through 2000. During the ‘90s the group developed a younger following thanks to headline appearances on the jam band-oriented H.O.R.D.E. Festival.

However, the guitarist’s increasing unreliability – which included a brief ejection from the act following a 1993 scuffle with police at a tour stop — and mounting friction between him and a now clean and sober Allman resolved itself when the band informed Betts via fax that he would be replaced by another guitarist on the next tour. A suit filed by Betts was settled in arbitration, ending his tenure with the Allman Brothers Band. Betts declined an offer to rejoin the Allman Brothers Band for their 40th anniversary tour in 2009.

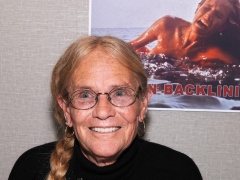

Betts reconciled with Allman before the singer-keyboardist’s death from liver cancer complications from in 2017, and attended his funeral.

The majority of Betts’ latter-day solo recordings were live affairs, and he continued to tour. He quietly retired in 2014, but returned to the road in 2017, saying he got “bored as hell.” In August 2018, he cancelled several concert dates after what was described publicly as a “mild stroke.”