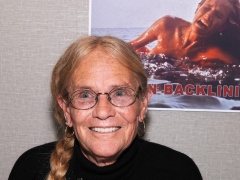

Musician John Mayall, often referred to the “godfather of the British blues,” whose bands of the late ’60s and early ‘70s featured some of the most notable rock instrumentalists of the era, died Monday at home in California, according to a statement posted by his family on his social media accounts. He was 90.

Among the fans and organizations posting condolences was the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which was set to induct him into its ranks in October. Although he was not part of the standard voting round, the hall’s committee had selected him this year to be ushered in under the Musical Influence Award, along with Alexis Korner and Big Mama Thornton.

No cause of death was given in the family’s initial statement, although it did refer to Mayall’s recent health setbacks. “It is with heavy hearts that we bear the news that John Mayall passed away peacefully in his California home yesterday, July 22, 2024, surrounded by his loving family,” the statement read. “Health issues that forced John to end his epic touring career have finally led to peace for one of this world’s greatest road warriors.”

‘Deadpool & Wolverine’ Underscores MCU’s Much-Needed Evolution

'The Simpsons' Reveals Upcoming 'Venom' Parody, Shares Video of Kamala Harris Reciting a Famous 'Treehouse of Horror' Quote at Comic-Con Panel

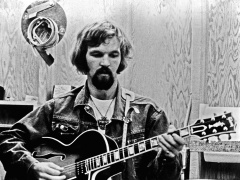

Mayall, whose keening, jazz-inflected tenor vocals reflected the heavy influence of the American singer Mose Allison, fronted his group – known variously as the Blues Breakers or Bluebreakers in its earliest incarnation – on keyboards, harmonica and occasional guitar, and penned dozens of original songs. Among the players he brought into his bands were such legends as Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Mick Taylor, Jack Bruce, John McVie, Mick Fleetwood and Aynsley Dunbar.

He was perhaps best known in America for the song “Room to Move,” a staple on FM radio in the early ’70s.

That was the song Mayall chose to end his touring career with, at the close of his final concert, which took place March 26, 2022 at the Coach House in San Juan Capistrano, Calif.

Many of the blues masters who paved the way for Mayall offered him praise for his keeping the genre in the limelight. “John Mayall, he was the master of it,” said B.B. King, saying that if it weren’t for him and other British musicians of his prime era putting their own spin on the blues, “a lot of us Black musicians in America would still be catchin’ the hell that we caught long before.”

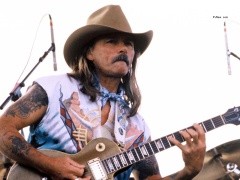

Musicians attested to what it meant to play with Mayall. “As far as being a blues-guitar sideman, the Bluesbreakers gig is the pinnacle. That’s Mount Everest,” said Walter Trout. “You could play with B.B. King or Buddy Guy, but you’re just gonna play chords all night. This guy features you. You get to play solos. He yells your name after every song, brings you to the front of the stage, and lets you sing. He creates a place for you in the world.”

“The reason I choose musicians is what they bring to the table, and I enjoy their work, and I want to give them an opportunity to express themselves because that’s what I hired them for,” Mayall said in a 2016 interview with Blues Blast. “So I enjoy their playing and fortunately, being a bandleader, I get to choose who I want to play with. So, I indulge my own musical enjoyment. … Improvisation is the main thing. You have your structure of the musical piece, and then you embellish it in whatever direction that evening’s performance entails. So, it’s always been the bedrock of everything I’ve done. The whole idea is to create music as you’re playing. The improvisational thing is the main part of it. You’re exploring the music.”

Beginning his pro career in in London during the early ‘60s among such purist Brit-blues bandleaders as Alexis Korner (an early sponsor in the English blues clubs), Cyril Davies and Graham Bond, Mayall featured front line players who were among the cream of the highly competitive blues scene.

His own talents were often overshadowed by the legendary musicians who played behind him. Between 1965 and 1969, he employed in succession three staggeringly gifted lead guitarists: Clapton, Green and Taylor.

Clapton exited Mayall’s unit to found the rock supergroup Cream with bassist Jack Bruce (another of his sidemen) and drummer Ginger Baker. Green himself bowed out of the Bluesbreakers to form Fleetwood Mac with Mayall’s onetime rhythm section of Fleetwood and McVie. And, on Mayall’s recommendation, teenage phenom Taylor replaced Brian Jones in the Rolling Stones.

For years, Mayall’s blues-rock outfit prevailed as a distinguished finishing school on the order of Miles Davis’ jazz bands. Other vets enjoyed noteworthy careers on their own: saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith, bassist Tony Reeves and drummer Jon Hiseman founded the horn-driven jazz-rock band Coliseum, while acoustic guitarist Jon Mark and flutist-saxophonist Johnny Almond formed their own eponymous unit.

During the Mark-Almond era – a unique period in which Mayall eschewed the use of a trap drummer – the musician released what was probably his best-known American single, the riff-based “Room to Move”; the live album from which it was drawn, “The Turning Point,” was his lone LP to achieve gold status.

In the early ‘70s, Mayall relocated to Los Angeles, where he worked with such notable American blues players as guitarist Harvey Mandel, violinist Don “Sugarcane” Harris and bassist Larry Taylor. A 1970 album featuring them, “USA Union,” peaked at No. 22, the bandleader’s highest chart position.

Mayall achieved his greatest eminence as a front man and touring presence in the early ‘70s, but he remained a tireless road warrior for decades, playing concerts into his 80s. In 1982, he reunited with Mick Taylor and John McVie for a lengthy world tour.

A new edition of the Bluebreakers, founded in 1984, featured a fierce two-guitar lineup of Coco Montoya and Walter Trout that incited new interest in Mayall’s music. He also landed a high-profile label deal with Silvertone Records, the U.S. label that refreshed Buddy Guy’s blues career.

Mayall began the new millennium with a milestone-marking, celebrity-filled album, “Along for the Ride,” and a 70th-birthday concert in Liverpool that reunited him with Clapton and Taylor. His latter-day bands included such top guitarists as Sonny Landreth, Robben Ford and Carolyn Wonderland.

He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 2005, and was inducted into America’s Blues Hall of Fame in 2016.

He was born Nov. 29, 1933, in the midlands city of Macclesfield. His father was an amateur guitarist and jazz enthusiast, and young Mayall fell under the sway of American jazz and blues stars as a youth, teaching himself piano, guitar and harmonica.

After an army stint, Mayall enrolled in Manchester College of Art; his design training there later served him – he painted the band portrait for the cover of his 1967 album “A Hard Road” and crafted the look of 1969’s “The Turning Point.”

While in school, he formed some semi-professional groups that performed locally and jammed at local all-nighters. After meeting Alexis Korner, the foremost exponent of the early-‘60s British blues sound, at a Manchester date, the older musician took him under his wing; in 1963, he began playing in London with the first edition of the Bluesbreakers.

A debut live album for Decca Records featuring Mayall, McVie, drummer Hughie Flint and guitarist Roger Dean failed commercially, but the Bluesbreakers’ fortunes soared with the addition of the Yardbirds’ dissident lead guitarist Clapton, a rising rock star who was seeking a more purist environment for his playing.

The second Bluesbreakers album, featuring Clapton, reached the top 10 in the U.K. in 1966 and became a cult hit in the U.S. However, the guitarist seemed unable to commit full-time to Mayall’s group, and by 1967 he had been displaced by Peter Bardens’ lead guitarist Peter Green, who flexed a similarly powerful Chicago-style electric attack.

“A Hard Road” was a potent showcase for Green, whose album-closing instrumental “The Super-Natural” served as a blueprint for his later composition “Black Magic Woman.” But his time with Mayall was also short-lived, and he wooed his bandleader’s rhythm section to form an even harder-edged blues-rock combo, Fleetwood Mac.

Prodigious 18-year-old Mick Taylor, who had fatefully sat in with the Bluesbreakers after Clapton failed to show for a 1965 date near London, was recruited to fill Green’s slot. He appeared on four Mayall albums between 1967 and 1969. Mayall himself magnanimously suggest Taylor as Brian Jones’ replacement in the Stones.

After several clamorous years of electric blues power, Mayall abruptly ratcheted down the volume for two albums with Mark and Almond. Though it failed to climb above No. 102 in the States, the novel single “Room to Move” remained Mayall’s best-recalled tune thanks to plentiful FM airplay; another track featuring the Mark-Almond combine, “Don’t Waste My Time,” peaked at No. 81 in 1970.

Besides “USA Union,” Mayall’s most distinctive recordings of his early American epoch included “Back to the Roots” (1971), featuring an all-star ensemble including guests Clapton and Taylor, and “Jazz Blues Fusion” (1972), a self-descriptive live set with the American jazz and R&B instrumentalists Blue Mitchell and Clifford Solomon.

In September 1979, a fast-moving brush fire in L.A.’s Laurel Canyon destroyed Mayall’s home and consumed all his possessions, including what was reputed to be one of the world’s largest and most valuable collections of vintage pornography.

Mayall recorded prolifically for Polydor and ABC, among others, through the ‘70s and ‘80s with no commercial traction. His Silvertone releases “Wake Up Call” (1993) and “Spinning Coin” (1995) briefly returned him to prominence.

“Along for the Ride” proved his highest-profile release in years, uniting him with such guitar-slinging ex-band mates, peers and acolytes as Green, Taylor, Otis Rush, Gary Moore, Steve Cropper, Steve Miller, Billy Gibbons, Jeff Healey and Jonny Lang.

In 2019, he released “Nobody Told Me,” an album that was described as being recorded shortly before a “health scare.” Guests on this penultimate effort included Todd Rundgren, Little Steven Van Zandt of the E Street Band, Alex Lifeson from Rush and Joe Bonamassa.

His final studio album was 2022’s “The Sun Is Shining Down,” which included such boldface-name guests as Mike Campbell, Marcus King and Buddy Miller. Wrote Thom Jurek in a review for Allmusiccom, “Hopefully, life goes according to plan and Mayall gets to deliver many more recordings before he’s done, because ‘The Sun Is Shining Down’ sounds hungry and vital. Mayall delivers these rough-and-ready blues like a champ.” This final effort was nominated for the 2023 Grammys in the category of best traditional blues album.

When Mayall was named as an inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in April, his social media accounts said that he was was pleased to be going into the hall alongside Alexis Korner, “who, back in 1963, suggested that a living could be made playing the blues in London.”

In a 2016 interview with Blues Blast magazine, Mayall reflected on the benefits of his level of fame and notoriety. “I mean, it’s still an acquired taste for my listening public, and they’re not of sufficient numbers to put me on the charts or put me in the news in any way,” he said. “So I’m still pretty much of an outsider in that respect, so I just go my own way and hope for the best. Bt we just have a great time playing — which is just an enviable situation, because people in big hit groups and everything, they’re kind of stuck with what they’ve made famous, and they’ve lost the opportunity to improvise and explore.”

Mayall is survived by his six children — Gaz, Jason, Red, Ben, Zak and Samson — along with seven grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. His death announcement also mentioned the support of his previous wives, Pamela and Maggie, and a devoted secretary, Jane.