Ian Tyson, a towering figure in Canadian music who found his greatest renown as half of the ’60s folk-singing duo Ian and Sylvia, died Thursday at 89. The cause of death was attributed to “ongoing health complications.”

Ian and Sylvia’s most famous song, the Tyson-penned “Four Strong Winds,” released in 1963, became a folk standard. It has been covered by dozens of artists over the last six decades, among them Neil Young (on his “Comes a Time” album), Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, John Denver, Teenage Fanclub, the Carter Family, Marianne Faithful, Waylon Jennings, Bobby Bare, Gillian Welch and Conor Oberst. In 2005, CBC listeners voted “Four Strong Winds” the most essential Canadian piece of music.

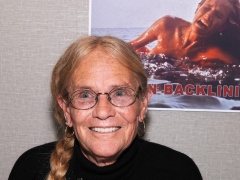

Tyson began singing with his future wife, Sylvia Fricker, as Ian and Sylvia in the early 1960s, and they became a critical part of the New York folk scene alongside emerging figures like Dylan, whose manager, Albert Grossman, took them on, as they signed to the Vanguard label. The two singers married in 1965 and divorced in 1975 after releasing 13 albums together. (They have often been cited as the closest analog for the fictional “Mitch and Mickey” singing duo in the satirical “A Mighty Wind” film.)

In the very early ’60s, original material was not considered essential on the New York folk scene, with even Dylan’s debut album consisting mostly of covers. Tyson remembered how that suddenly changed in a big way in 1962, recalling how Dylan “sang me ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ — he’d just wrote it. And I thought: ‘I can do that’ …He wrote ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ and the next day I wrote ‘Four Strong Winds’.”

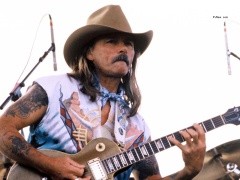

Following the martial and professional split between Ian and Sylvia in the ’70s, Tyson reinvented himself back in Canada, as someone devoted to the ranching lifestyle in a small town near Alberta, and as a solo artist focusing more on Western-style, often cowboy-themed music. It was not a complete left turn, musically, given that Ian and Sylvia had moved their base to Nashville for a period in the late ’60s and formed the group Speckled Bird, considered a pioneering force in the burgeoning country-rock movement. But as he focused on his new solo music, Tyson had little lingering interest in the folk scene, rock ‘n’ roll or even mainstream country music, preferring to focus on music that reflected his passion for wide open spaces.

“I always wanted to be a cowboy — not a songwriter or a singer, a cowboy. I just got lucky in the music business,” Tyson told the website Cowboy Showcase in 2008.

“It’s like I had two careers,” Tyson further said in an interview with Folkworks‘ Terry Roland in 2009. “There were the Ian and Sylvia days and then this new music, which had no association to ‘60s music. It was kind of nice. But I’ve found a way to bring back the Ian and Sylvia music as well in my recent shows. It’s like you can’t just drop all of that, it has to be in there somehow. … I was identified with the name Ian and Sylvia. My acceptance happened after I’d reinvented myself in an authentic way. I came to be so identified with that period of my career, it was hard to walk out of the shadow of that. But, finally, I was able to move on.”

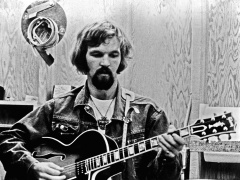

Tyson did not just adopt the rural lifestyle later in life. He participated in the rodeo circuit for several years beginning when he was 18, and didn’t begin his music career until he was 24. In Vancouver, he was the rhythm guitarist in a rockabilly band called the Sensational Stripes, which he recalled sharing a bill with Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, LaVern Baker and Paul Anka in Vancouver in 1956.

Ian and Sylvia achieved mainstream popularity through TV shows like “Hootenanny,” which Tyson called “a dreadful show — appalling.” Of the duo, Tyson told the Classic Bands website in 2005, “We had a sound that was pretty unique. It was pretty vibrant for a couple of years, then it just kind of fell apart. It was based on our vocal blend. It wasn’t like anybody. It was pretty unique. We made a couple of great albums. Then the albums got un-focused and the direction got strange and then pressure from the record companies to get a radio hit and pressure from ourselves. We wanted it too. Everybody was getting hits. We almost got one. You know, just couldn’t stand the stress.”

While “Four Strong Winds” was the first song Tyson wrote, after the duo got its start doing covers, Sylvia Tyson’s first contribution as a songwriter was “You Were on My Mind,” which became a hit via a cover version by the We Five.

Ian Tyson said that the British Invasion “killed the Folk movement. I would say the California rock scene killed it just as potently. Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe and the Fish… all that San Francisco stuff. That shut down the folk thing. Totally shut it down. … Folk came back stronger than ever. And it is stronger. It has out-lasted San Francisco rock, acid rock and all that shit. Folk will always be around. In those days we thought it was the apocalypse. People didn’t want to listen to what they thought was folk. Who the hell knows what folk is? But, they didn’t want to listen to that stuff. That’s fine. We all had to find something else to do.”

Of the contrast between his old and new styles, and fans’ expectations in concert, Tyson said in 2005, “I don’t do nostalgia. I’m a writer and I keep writing. Some people get frustrated, they want to hear nothing but the old stuff, but I have never given them just the old stuff. Never. They gotta listen to new stuff at least half of the evening. If they don’t want to listen to it, they don’t have to come back again, but they do come back again. So, I guess in the final analysis, the approach I’ve taken has given me longevity.”

His solo albums included “18 Inches of Rain,” “Cowboyography,” “Songs Along a Gravel Road” and “Yellowhead to Yellowstone and Other Love Stories.” Tyson also worked extensively with fellow singer-songwriter Tom Russell. He wrote a children’s book, “Primera: The Story of the Mustangs.”

Tyson told Folkworks that the subject of the vanishing West was “covered in most of my songs. It’s a big part of what I do. There’s a sense of solitude that many of us feel who are from these parts of the world. The more populations come in, the less this culture will survive. For younger people today who are in the ranching culture, this way of life is really under attack. The lifestyle starts to disappear because of the population increase; that big, empty, romantic West disappears. You know, in California, there’s a lot of open country, especially at the northern end of the state. But the West you and I love and grew up with can’t sustain itself. It gradually is becoming something else.”