Singer-pianist Jerry Lee Lewis, the hell-raising, larger-than-life rock ‘n’ roll pioneer and latter-day country star, has died, according to a rep, Zach Farnum. He was 87.

His death had erroneously been reported by some outlets on Wednesday.

“Judith, his seventh wife, was by his side when he passed away at his home in Desoto County, Mississippi, south of Memphis,” Farnum’s statement said. “He told her, in his final days, that he welcomed the hereafter, and that he was not afraid.”

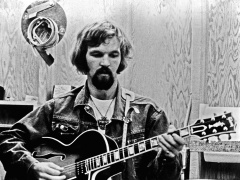

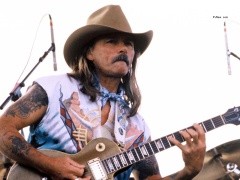

Lewis — an inaugural inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986, a 2005 recipient of a Recording Academy Lifetime Achievement Award and, at the age of 86, a 2022 inductee of the Country Music Hall of Fame — was a powerhouse keyboardist, mercurial vocalist and rampaging, unpredictable showman who could master virtually any song, be it rock ‘n’ roll, country, R&B, gospel or pop.

Lewis ultimately transcended category. With typical arrogance, he would frequently declare that there were only four real stylists in American music: Al Jolson, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams and, of course, Jerry Lee Lewis.

The late journalist Nick Tosches, Lewis’ great Boswell, captured some of his titanic dimensions in his book “Country,” published in 1977 during his country resurgence: “Believe it: Jerry Lee Lewis is a creature of mythic essence….He was — and in a way still is — the heart of redneck rock ’n’ roll, and one of the greatest country singers who ever lived.

“He is the last American wild man.”

In 1958, at the age of 22, after he attained national success with his pounding rockabilly singles “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” and “Great Balls of Fire,” his career hit the wall with the scandalous revelation of his marriage to his 13-year-old cousin. It took him a decade to regain his commercial footing with a series of powerful honky-tonk ballads.

Known universally by the self-established sobriquet “the Killer,” Lewis was notorious for his drinking, drugging, womanizing and pistol-waving pugnacity. The opening epigraph in Tosches’ classic 1982 biography “Hellfire” is a quote from the musician: “I’m draggin’ the audience to hell with me.”

Yet, for all his well-documented excesses and dark, lurid history, listeners returned to embrace him over the course of seven decades.

Despite sustaining a hedonistic pace that would kill lesser men, he outlived all his ‘50s contemporaries, including Elvis Presley, whom he followed to fame at Memphis’ Sun Records in 1957.

He was born Sept. 29, 1935, in Ferriday, La. (hence his early professional nickname, “the Ferriday Fireball”), and began playing piano at the age of nine. As a boy, he hung out at Haney’s Big House, a local honky tonk, with his cousins, evangelist-to-be Jimmy Lee Swaggart and future country singer and club owner Mickey Gilley. His principal keyboard influences were country boogie stylist Moon Mullican, Nashville barrelhouse pianist Del Wood and San Diego-bred boogie-woogie player Merrill Moore.

In 1952, during a trip to New Orleans, 16-year-old Lewis cut his first demos — a Lefty Frizzell cover and an original off-the-cuff boogie instrumental — at Cosimo Matassa’s storied J&M Studio on Rampart Street. By his late teens, he was working at the Blue Cat Night Club in Natchez, MS, and fronting a 20-minute weekend radio show there. A horrendous student, he dropped out of high school; his frustrated mother enrolled him in an Assembly of God Bible school in Texas, from which he was swiftly expelled for applying boogie-woogie to the hymnal.

He married twice in his teens, and fathered a son by his second wife: Jerry Lee Lewis, Jr., who would drum behind his father before he was killed in a single-car accident in 1973.

Summarily rejected by Slim Whitman when he applied for a touring unit of Shreveport’s Louisiana Hayride, Lewis drove to Memphis in early 1956 to audition at Sun Records. The label had recently sold Presley, its star act, to RCA Records for $35,000, and had become a magnet for every aspiring hillbilly singer in the South.

Lewis impressed Jack Clement, Sun’s engineer and second-in-command to owner Sam Phillips, sufficiently enough to secure an opportunity to record for the label. He cut a couple of singles — his debut release was a cover of Ray Price’s country hit “Crazy Arms” — and contributed studio support to other Sun acts.

On Dec. 4, 1956, he was at Sun’s Union Avenue facility when Presley returned; an impromptu date with Sun’s then-current star Carl Perkins and Lewis (but minus label mate Johnny Cash, who dropped by for a photo opportunity only) later gained fame as the “Million Dollar Quartet” session.

Lewis did not have to wait long for his own fame to arrive. In March 1957, Sun issued “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” his version of a song by honky-tonk singer-pianist Roy Hall that had been covered by R&B shouter Big Maybelle. Billed to “Jerry Lee Lewis and His Pumping Piano,” the throbbing, boogie-woogie-inflected single scored on three charts – country (No. 1), R&B (No. 1) and pop (No. 3).

An attempt to cut a follow-up number penned by Otis Blackwell that October sparked a furious argument between Lewis and Phillips about the nature of sin that was recorded and later frequently bootlegged. The pianist finally acquiesced and recorded “Great Balls of Fire,” which climbed to No. 3 on the pop and R&B charts and reached No. 1 on the country chart.

Lewis captured national attention with a frenzied performance on “The Steve Allen Show” and caught hits in early 1958 with “Breathless” and “High School Confidential”; he appeared on screen in the latter song’s namesake exploitation picture, banging out the tune on the back of a flatbed truck.

He looked unstoppable, but Lewis’ roll ended abruptly after word surfaced during a May 1958 British tour that he had married Myra Gale Brown, the 13-year-old daughter of his bassist J.W. Brown and his first cousin once removed. The validity of his second divorce was also called into question. Lewis’ maladroit interviews with scandal-loving Fleet Street journalists did not quell the public tempest. He was pilloried by the press overseas, and then at home.

An open letter from Lewis that ran as an ad in Billboard that June began, “I have in recent weeks been the center of a fantastic amount of publicity, of which none has been good….I hope that if I am washed up as an entertainer it won’t be because of this bad publicity.”

Lewis saw his records expire from lack of airplay, and suddenly found himself banished to the seediest clubs in America. Sun even attempted to sneak Lewis’ instrumental “In the Mood” by the public under the pseudonym “The Hawk,” but the ploy fooled no one. To most record buyers, he was poison.

Lewis remained with Sun until 1963, the year after his son Steve Allen Lewis drowned in the family pool. That year, he was signed to Mercury Records. His rockabilly-styled singles for the Smash subsidiary found little favor.

His best records of the period were live shots, the finest of which was a manic 1964 set (originally only issued overseas) backed by England’s Nashville Teens and recorded before an amped-up, chanting crowd at Hamburg’s raucous Star-Club, the notorious Reeperbahn venue that had hosted the Beatles in their salad days.

In “Lost and Found,” his 2009 book about the album, Joe Bonomo called it “one of the most honest and shockingly rocking albums ever made, by a man who many in his own homeland considered a stained and wicked has-been during a brutal passage in his career where he had to dig deep to find what moved him.”

After five fruitless years at Mercury, Lewis finally struck pay dirt when producer Jerry Kennedy began recording the renegade rocker in a pure honky-tonk format. Starting with “Another Place Another Time,” No. 4 in 1968, Lewis racked up a string of 13 top-five country singles over a three-year period. Four of them – “To Make Love Sweeter For You,” “There Must Be More to Love Than This,” “Would You Take Another Chance On Me” and a remake of the Big Bopper’s “Chantilly Lace” – topped the chart. Over the course of his career, he placed 63 singles on the U.S. country chart.

In the 1995 oral biography “Killer,” written with Charles White, Lewis said of his stylistic expansiveness, “I had the audience kinda mixed up for a while. They knew I was a rock ’n’ roll singer so they didn’t know what to make of all this country stuff. On tour we always went back to ‘Great Balls of Fire’ and ‘Whole Lotta Shakin’.’ No matter how many country hits I had I always went back to rock ’n’ roll ‘cause that’s what people want, and that’s what I do best.”

In 1970 — in what many saw as a transparent attempt to salvage his crumbling marriage — a momentarily penitent Lewis abandoned country, proclaimed himself “saved” and recorded a pair of gospel albums. He was playing country music again within weeks, and Myra Gale filed for divorce that year. Lewis piled up several lesser country hits as the ‘70s progressed, and issued the requisite all-star London date “The Session” in 1973.

His transgressive behavior regularly captured the headlines. In 1976, after wrecking his Rolls-Royce in a drunk-driving accident, he was arrested, intoxicated, with a loaded derringer on the grounds of Elvis Presley’s Graceland estate. The same year, he shot his bassist Butch Owens in the chest with a .357 Magnum handgun; Owens survived, and only minor charges were filed. Failure to pay income taxes for years led to a 1979 raid on Lewis’ home by the Internal Revenue Service. Thanks to a variety of alcohol-related ailments, he bounced in and out of hospitals for years, losing a third of his stomach to ulcer surgery in 1985.

Amid the chaos, he managed to sustain a career. A 1979-80 sojourn at Elektra Records yielded the latter-day signature “Rockin’ My Life Away,” a heartfelt No. 10 cover of the dreamy “Wizard of Oz” standard “Over the Rainbow” and the No. 4 mid-life lament “Thirty Nine and Holding.” A ‘80s stint with MCA produced no hits, but Lewis garnered attention in 1986 when he returned to Sun Studio for “Class of ’55,” a reunion album on Smash that also featured Cash, Perkins and Roy Orbison.

In 1989, Lewis recorded the music for Jim McBride’s biopic “Great Balls of Fire,” drawn from ex-wife Myra Gale’s caustic depiction of their life together; he was portrayed, unconvincingly, by Dennis Quaid. Its subject was reportedly not fond of the picture.

Except for “Young Blood,” a tortuously completed 1995 album for Sire Records, Lewis contented himself with live performing until 2006, when the all-star duets set “Last Man Standing” was issued by multi-millionaire Steve Bing’s Shangri-La Music.

In the 2015 edition of his 1975 book “Mystery Train,” Greil Marcus wrote of the seemingly indestructible performer’s comeback, “Lewis’ death has been announced any number of times over the years, which gave him the chance, in 2006, to spit at the world with ‘Last Man Standing.’”

A pair of similarly styled sequels followed: “Mean Old Man” (2010) and “Rock & Roll Time” (2014). A 2019 stroke sidelined him and affected his ability to play the piano, but a 2020 news report said he would record vocals on an album of gospel music for producer T Bone Burnett.

In 2014’s “Jerry Lee Lewis: His Own Story,” he asked his biographer Rick Bragg, with some understatement, “I’ve had an interestin’ life, haven’t I?”

Lewis is the subject of the 2022 critically acclaimed documentary “Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind” from director Ethan Coen — his first solo feature — and producer T Bone Burnett.

Last weekend, Lewis posted on Instagram that he was too sick to attend his Country Music Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

“It is with heartfelt sadness and disappointment that I write to you today from my sick bed, rather than be able to share my thoughts in person,” Lewis wrote. “I tried everything I could to build up the strength to come today — I’ve looked so forward to it since I found out about it earlier this year. My sincerest apologies to all of you for missing this fine event, but I hope to see you all soon.”

ned="" data-instgrm-permalink="https://www.instagram/p/Cj6eS8KgV8o/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading" data-instgrm-version="14">A post shared by Jerry Lee Lewis (@jerryleelewisthekiller)

Divorced by Myra Gale in 1970, Lewis remarried four times. Wife Jaren Pate drowned in 1983. A two-month marriage to Shawn Stephens ended with her fatal drug overdose in 1984. Sixth spouse Kerrie McCarver divorced him in 2004. He wedded his caregiver, Judith, in 2012.

He is survived by his wife, his children Jerry Lee Lewis III, Ronnie Lewis, Phoebe Lewis and Lori Lancaster, sister Linda Gail Lewis, cousin JimmySwaggart and many grandchildren, nieces and nephews.

Donations may be made in Jerry Lee Lewis’ honor to the Arthritis Foundation or MusiCares – the non-profit foundation of the GRAMMYs / National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.