Alabama looked like us. Jeans, T-shirts and sneakers; they were working class and basic as they come. But what the 2005 Country Music Hall of Fame inductees had back when they created a new kind of country was a rock swagger that brought big arena-filling energy to a genre that was most often polite, twangy in extremis and unrelatable to pop music fans.

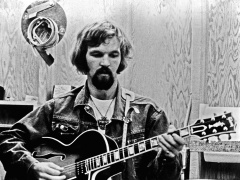

Jeff Cook, the multi-instrumental lead guitarist and harmony singer, was a big part of that. Whether the fiery violin break on “If You’re Gonna Play In Texas (You Gotta Have A Fiddle in the Band),” the double-necked guitar brought out for extended guitar solos or the signature licks on “Mountain Music,” one of the band’s breakthrough hits, the Fort Payne-born and -raised player understood how to slice into country music with a charge that was as electric as it was hooky.

For a new generation of young people, who couldn’t relate to their parents’ post-“Urban Cowboy” country, Alabama brought a punch that caught them squarely in their concert-going desires. They headlined the biggest fairs, major arenas and — when they thought the buildings weren’t being square with them — fields set up like today’s festivals, breaking records and luring thousands of young people or the country band that looked like the kids that came to see them across the nation.

As a young critic at the Miami Herald, raised on rock ‘n’ roll in Cleveland, I was shocked by their aesthetics. They had the same torque as the Doobie Brothers, REO Speedwagon and other rock bands of the day, only their hooks were bigger. Jeff Cook launched legions of air guitar-playing young men, rocking out to… well… country music.

Reviewing them meant seeing not with “country music” eyes, but through a rock prism that was willing to accept themes that embraced Southern living, values and aesthetics. Hosting pre-concert press conferences whenever they came to a town, Cook always got questions about gear. It made the rest of the band laugh, the more general critics not sure what to do with the information about pedal boards or string gauges.

And Jeff Cook was good with that. Like Randy Owen, Teddy Gentry and Mark Herndon, the goateed guitarist was all about the people, or more the fans. They’d sign autographs, pose for pictures and share memories with the people who loved their music for hours some nights — always recognizing the magic it was for the person they might be speaking to.

Beyond the annual June Jam concert, held in Fort Payne to benefit where they came from, held every year on the back-end of Nashville’s Fan Fair (now CMA Music Fest), they were always willing to show up for charities, or causes they felt passionate about. Make-a-Wish, St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital in Memphis and so many more were beneficiaries of their generosity.

In the late ’80s, long before climate change was a hot topic, they recorded “Pass It On Down,” a song suggesting leaving the planet a better place. For a bunch of cousins from Fort Payne, dialing into something like that would seem alien to the average music person.

Standing around an oil drum with a fire lit to keep people warm on an all-night video shoot, Cook and Owen talked about their kids and eventually their own children’s children; how being hunters and appreciating nature, they realized if we didn’t care for this world, we would leave a planet in crisis on its way to being uninhabitable.

“It’s all connected,” Cook said, simply. Not as a scientist, an activist or even a politician, just a common-sense human being, who wanted to use his fame to maybe raise people’s consciousness without preaching or lecturing.

That was the band’s, and the guitarist’s, way. Be of the people, lift them up, make them sing, let them dance. Whether it was the Muscle Shoals eroticism of “Love in the First Degree,” the sinewy guitar-threaded homage “My Home’s in Alabama,” the beachy innocence of “Dancin’, Shaggin’ on the Boulevard,” the daredevil speed of “Dixieland Delight” or the working man’s “40 Hour Week,” Jeff Cook’s guitar lines were as recognizable as Alabama’s three-part blood harmony.

In that, country music got a breath of fresh air — and new blood. In a 2019 appreciation for Pollstar, Kenny Chesney wrote, “I’d never been out of the county. But here was this band who understood us, how we lived and what we felt. It was in their songs! They were ours… The way they looked, and the way they attacked the music. It was genre-less, but it was also everything we were. They were our Beatles, because that’s how big they were to us. And they reflected our lives. I don’t think it’s possible for me to ever tell them the impact they had on me.”

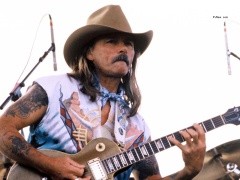

Indeed, had on an entire genre of music. When on one hand you had bad boys like Hank Williams, Jr, Johnny Paycheck and David Allen Coe, who rocked, and on the other hand you had everybody else who your (grand)parents might love, Alabama understood the regular kids — incoming fans who were ready for a country music that was neither old-fashioned nor the soundtrack for an ass-whupping. Like the 30,000 people I once stood in a field with because the arena the rock acts played wouldn’t give the band the same deal, it was all about being there, being alive and knowing nothing else was necessary. They kicked out the jams, but wore boots or Adidas doing it.