The Doobie Brothers announced the death of drummer John Hartman Friday, collectively saying in a social media post, “Today we are thinking of John Hartman, or Little John to usJohn was a wild spirit, great drummer, and showman during his time in the Doobies.” He was 72. No cause of death was immediately announced.

Hartman, a co-founder of the group, was one of nine members of the Doobie Brothers inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020. He had long since left the frequently reuniting band.

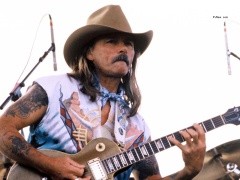

Hartman was with the group for its initial run of chart-topping hits, including signature songs like “Listen to the Music,” “Long Train Runnin'” and “What a Fool Believes.” He was one of two drummers the Doobies had on stage from 1971 until he first left the band in 1979. Ten years after departing, he returned for a reunion album in 1989 and continued on with the group through 1992.

ned="" data-instgrm-permalink="https://www.instagram/p/Ci0mzaYOr8_/?utm_source=ig_embed&utm_campaign=loading" data-instgrm-version="14">A post shared by The Doobie Brothers (@doobiebrothersofficial)

The band is currently in the midst of a 50th anniversary tour, including a stop tonight in Portland, but Hartman was not taking part in the reunion. Michael McDonald, Tom Johnston, Pat Simmons and John McFee are the four legacy members advertised as participating in the current tour.

Hartman looked beyond the world of music to law enforcement for a career after leaving the Doobie Brothers for a second time. In 1994, the New York Times reported that he was seeking a career as a full-time police officer, but was “finding that goal impossible to reach because of his first job,” having admitted to drug use during his time in the Doobies (which were named after slang for marijuana). At the time of the article, Hartman had graduated from a police academy and worked for a police department for three years, but said 20 police departments in the northern California area had rejected him for a job. HIs discrimination lawsuit against the Petaluma Police Department was dismissed.

Hartman said at the time that his drug use had gone too far in the mid-1970s, but that after being confronted by other band members — some of whom had their own problems with the substance abuse that was rampant in the era — he quit using drugs altogether in 1975. “I’ve picked myself up from the sewer,” Hartman told the Times about his cessation of substance abuse a few years into the band’s career.

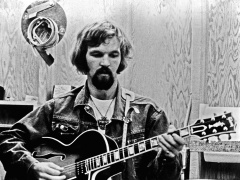

In a 1973 interview with Cameron Crowe for Rock magazine, Hartman described himself as the leader of the group, and he was further characterized as “owner of the title ‘the white Buddy Miles.'” Crowe wrote that Hartman, who at times could have been mistaken for one of the Hell’s Angels that used to come to the shows during their humble early gigs, “is fascinated with his own menacing physique. He uses it to his advantage, too. Orlet’s put it this way . . . he tries,” describing Hartman jokingly trying to intimidate the teen rock journalist during an interview.

Hartman was ebullient at the group having escaped the club scene with its suddenly monstrous AM-FM hits. “Am I anxious to get back to playing bars and clubs again?” he told Crowe in 1973. “Let me put it this way . . . if you were driving a Volkswagen and you really wanted to be driving a Cadillac, and you finally got that Cadillac, would you want to go back to the VW? I mean who in their right mind would want to go back to a bar. Jesus . . . drunks and idiots, bad pay, no pay . . .”

Hartman, who moved to central California from the east coast in 1969, had been roommates with guitarist Tom Johnston at San Jose State, and when they met singer-guitarist Patrick Simmons, the core of the group came into shape, circa 1970. The first name of their band was Pud, and they got a residency of sorts at a bar called the Chateau Liberté, a one-time stagecoach stop in the Santa Cruz mountains with a biker clientele. “It was one of those places where you over-drink and step outside and throw up,” Hartman told Rolling Stone. “It was beautiful, man!”

After they got signed to Warner Bros., a debut album did only moderately well, and Hartman half-joked that it was because they put him and his rough-looking visage front and center on the first album cover, even though he was hardly the frontman of the band. The Doobies took off in ’72 when their second album, “Toulouse Street,” included the breakout hit “Listen to the Music.”

The band changed direction in 1976 with “Takin’ It to the Streets” as McDonald largely took over for Johnston. With different band members feuding, Hartman quit in 1979 at the same time as Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, later saying, “Everything was falling apart.” There was a farewell tour in 1982 before Hartman and the other original members regrouped for a reunion in 1989, minus McDonald.

Although there were plans for the original members to reunite for the Rock Hall induction in 2020, that ceremony was canceled and downgraded to a video presentation due to the pandemic.

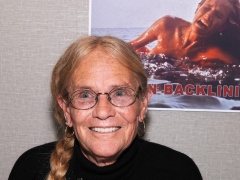

Interviewed at the time of their impending induction by Rolling Stone, Hartman, who had been out of the music business for close to three decades, laughed at the “yacht rock” tag, which he had never heard before. “Oh my God, that’s perfect!” he said. “I’ll be laughing for the next three weeks!”

A documentary on the group, “Let the Music Play,” was released in 2021, but reviewers noted at the time that Hartman was conspicuous in being the only major living figure from the group not interviewed for the film.

In 2021, the San Jose Historic Landmarks Commission voted unanimously to recommend landmark status for the craftsman house that Johnston and Hartman shared when the group was coming together in the early ’70s.

In Memoriam: As co-founder and original drummer of the Doobie Brothers, John Hartman delivered propulsive rhythms to theband's chart-topping songs that filled the 1970's airwaves. pic.twitter/YQof1wuslT

— Rock Hall (@rockhall) September 20, 2022