Bob Neuwirth, a recording artist, painter, mainstay of the New York City folk scene in the 1960s, and a collaborator with Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, John Cale and T Bone Burnett, among others, died in Santa Monica Wednesday night at age 82. The cause of death was heart failure.

“On Wednesday evening in Santa Monica, Bob Neuwirth’s big heart gave out,” said his longtime partner, entertainment executive Paula Batson, in a statement. “He was 82 years old and would have been 83 in June. Bob was an artist throughout every cell of his body and he loved to encourage others to make art themselves. He was a painter, songwriter, producer and recording artist whose body of work is loved and respected.

“For over 60 years, Bob was at the epicenter of cultural moments from Woodstock, to Paris, ‘Don’t Look Back’ to Monterey Pop, ‘Rolling Thunder’ to Nashville and Havana. He was a generous instigator who often produced and made things happen anonymously. The art is what mattered to him, not the credit. He was an artist, a mentor and a supporter to many. He will be missed by all who love him.”

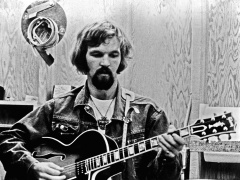

Neuwirth is seen above in a photo taken just two weeks ago by Larry Bercow.

Neuwirth took on many roles in his career in the arts, in and out of music, but Patti Smith may have encapsulated it best when, in her memoir, she described him as “a catalyst for action.”

In his memoir, “Chronicle: Volume 1,” Dylan wrote, “Like Kerouac had immortalized Neal Cassady in ‘On the Road,’ somebody should have immortalized Neuwirth. If ever there was a renaissance man leaping in and out of things, he would have to be it.”

In 1988, writing the liner notes for a Neuwirth album, T Bone Burnett took stock of Neuwirth’s place in the scene and called him “the best pure songwriter of us all.”

Neuwirth was not prolific in the albums he released over a 60-year career, often preferring work as a painter or supporting other artists’ visions as a producer, writer or bandleader, although he had resumed concert performances in recent years. In 1994, he and John Cale collaborated on the experimental album “Last Day on Earth,” on MCA. His series of solo albums began with a self-titled 1974 effort on Asylum.

He did not record a sophomore album for another 14 years, finally reemerging with “Back to the Front,” the 1988 album that included the aforementioned Burnett liner notes, made with Steven Soles, another veteran of the Rolling Thunder Revue. In the late ’90s, Neuwirth went to Havana and worked with famed Cuban musician Jose Maria Vitier on their album “Havana Midnight.”

Being part of Bob Dylan’s circle led to a certain kind of fame among that artist’s vast army of fans. Neuwirth is seen in the film “Don’t Look Back,” standing alongside Allen Ginsberg in the background of the “Subterranean Homesick Blues” proto-music-video. And he helped assembled the band for — and performed on — the Rolling Thunder Revue tour in the mid-’70s, which led to his also being featured in Dylan’s “Renaldo and Clara” film. In-between, he had toured with his close friend Kris Kristofferson.

Neuwirth was interviewed for Martin Scorsese’s 2005 Dylan documentary, “No Direction Home.” “Back then it wasn’t money-driven,” Neuwirth says in the film. “It was about if an artist had something to say. Whether it was Bob Dylan or Ornette Coleman, what people would ask was, ‘Does he have anything to say?'”

Among the things that help make up Neuwirth’s legend is that he co-wrote one of Janis Joplin’s most iconic songs, “Mercedes Benz,” for the singer shortly before her 1970 death. It became a posthumous hit and one of the songs she is most identified with – as well as a shower song for millions in her wake. “It’s a campfire song, isn’t it?” Neuwirth told this writer in a 2013 interview. “You don’t need any particular musical skill to sing it, and because it’s a cappella, everybody can tackle it in their own way. But I’m sure Janis would be shocked at the attention that that song has gotten over the years. She’d just be shaking her head in disbelief at it.”

In another unpublished interview, Neuwirth said, “Mercedes Benz’ came when Janis and I were both drunk between shows, and she just played it and people loved it. It was put onto her ‘Pearl’ album. They needed a filler because she hadn’t recorded enough for the album before she died.” Neuwirth was also responsible for introducing Joplin to the signature song “Me and Bobby McGee,” written by Kristofferson.

Neuwirth’s association with Pennebaker continued over a period of decades. After being part of “Don’t Look Back,” he was a key part of the making of “Monterey Pop” with Pennebaker and John Cooke. Recalled Cooke in an interview with Harvey Kubernik, “Bob Neuwirth was sort of helping Penne to decide what was hip enough to shoot.” They also worked together on the ill-fated followup documentary to “Don’t Look Back,” “Eat the document.”

Flash forward to the early 2000s, and as the soundtrack to the Coen brothers’ “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” took off and generated a wave of enthusiasm for early 20th century roots music, Neuwirth rejoined Pennebaker to co-produce the documentary “Down From the Mountain,” filmed at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville with the artists who made the music for the “O Brother” soundtrack. Neuwirth was the musical director on the concert tour that followed that featured the music of “O Brother” and “Cold Mountain.”

As his work continuing the impact of the “O Brother” music on the road and on film would indicate, Neuwirth was a close associate of T Bone Burnett from the Rolling Thunder Revue period onward. He co-wrote songs on the early albums of Peter Case, which Burnett produced.

In the late ’90s Neuwirth worked with the late Hal Willner on the Harry Smith Anthology all-star concerts that were documented as they took place at the Royal Festival Hall in London, St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn and UCLA’s Royce Hall. He also contributed a song to Willner’s all-star 2006 compilation “Rogue’s Gallery: Pirate Ballads, Sea Songs and Chanteys.”

In 2014-16, Neuwirth had developed a “Stories and Songs” show that he took to New York, Los Angeles and the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville. When Neuwirth went to the latter museum in 2018 for “Music Masters: A Conversation with Bob Neuwirth,” museum editor Peter Cooper wrote, “Neuwirth’s path has been less a line than a hodgepodge of glorious zig-zags, all existing within a giant circle of song…Whether in spite of or because of the hijinks, hokum and hell, Neuwirth’s music stands as a testament to a marvelous, rollicking life.”

Of the wide range of forms his work took, Neuwirth said, “It’s all about the same to me, whether it’s writing a song or making a painting or doing a film. It’s all just storytelling.”

Neuwirth was born in the Akron, Ohio area and began painting as a teenager, which eventually led him to the School of the Museum of Fine Art in Boston. After spending time living in Paris and soaking up classical art there, he returned to Boston and worked in an art supply store while learning how to play guitar and banjo. He became part of the Cambridge folk scene that included Joan Baez, Geoff Muldaur and others, soon performing in New York, Berkeley and San Francisco as well. He joined Dylan for the tour captured in “Don’t Look Back.” But he continued to keep his focus largely on visual art, moving to New York and becoming part of the scene that would convene at Max’s Kansas City, a group that included Andy Warhol, Larry Poons, Robert Smithson and Robert Raushenberg.

In 2011, his artwork, which had long been solely the province of private collectors, was exhibited at the Track 16 Gallery in Santa Monica in a show curated by Kristine McKenna titled “Overs & Unders: Paintings by Bob Neuwirth, 1964-2009.” The notes for that exhibition said that in the early ’60s, “he was producing quirky hybrids of Cubism and Surrealism. The ’70s found him exploring various experimental materials, and he went on to produce a series of wall works that straddled the zone between painting and sculpture, and a cycle of haunted landscapes that are poised between abstraction and figuration. Neuwirth’s work has grown increasingly lyrical and fluid over the course of his career, and in recent years he’s been producing exuberant, expansive pictures filled with space, light, and blazing color.”

In an interview with the Paris Review, Neuwirth said, “I know how people can get famous. They have to tickle the G-spot of their minds. But being anonymous is so much more powerful. You can get so much more done if you’re not worried about fame and fortune. You can get a lot done.”

Neuwirth is survived by Batson and his niece, Cassie Dubicki, and her family.