Jim Seals, who as part of the duo Seals and Crofts crafted memorably wistful 1970s hits like “Summer Breeze” and “Diamond Girl,” died Monday at age 80. No cause of death was immediately given.

Several friends and relatives confirmed the death. “I just learned that James ‘Jimmy’ Seals has passed,” announced his cousin, Brady Seals, a former member of the country band Little Texas, Monday night. “My heart just breaks for his wife Ruby and their children. Please keep them in your prayers. What an incredible legacy he leaves behind.”

Wrote John Ford Coley, “This is a hard one on so many levels as this is a musical era passing for me. And it will never pass this way again, as his song said,” he added, referring to the Seals and Croft hit “We May Never Pass This Way (Again).” Coley was a member of another hit duo of the era, England Dan and John Ford Coley, with Jim Seals’ younger brother, the late Dan Seals.

“You and Dan finally get reunited again,” Coley wrote. “Tell him and your sweet momma hi for me.”

With Jim Seals as the primary lead vocalist of the harmonizing duo, Seals and Crofts came to be the very emblem of “soft rock” with a run of hits that lasted for only about six years. Although none of the pair’s hits ever reached No. 1 on the Hot 100, their biggest songs were for a time as ubiquitous as any that did top the chart. “Summer Breeze” in 1972 and “Diamond Girl” in 1973 both reached No. 6, as did a more upbeat song in 1976, “Get Closer,” sung with Carolyn Willis.

Besides those three songs that reached the top 10 on the Hot 100, four more made it to the adult contemporary chart’s top 10: “We May Never Pass This Way (Again)” in ’73, “I’ll Play for You” in ’75, “Goodbye Old Buddies” in ’77 and “You’re the Love” in ’78.

Critic Robert Christgau called the duo “folk-schlock,” but Seals and Crofts had the last laugh — or would have, if crowing with vindication was part of the Baha’i way. Both members of the duo were deeply embedded in that peace-loving faith from the late ’60s forward.

The duo broke up in 1980, followed by a couple of very fleeting reunions in the early ’90s and early 2000s, which generated only one album after their original run, the little-noticed “Traces” in 2004, They never reembarked together on the kind of nostalgia-stoking package tours that would have seemed a natural for an act with so many well-remembered hits. But neither member showed a particularly heavy interest in chasing the limelight after the 1970s.

John Ford Coley shared his thoughts at length in a Facebook post. “I spent a large portion of my musical life with this man,” he wrote. “He was Dan’s older brother, (and) it was Jimmy that gave Dan and me our stage name. He taught me how to juggle, made me laugh, pissed me off, encouraged me, showed me amazing worlds and different understandings on life, especially on a philosophical level; showed me how expensive golf was and how to never hit a golf ball because next came the total annihilation of a perfectly good golf club, and the list goes on and on. We didn’t always see eye to eye, especially as musicians, but we always got along and I thought he was a bona fide, dyed-in the-wool musical genius and a very deep and contemplative man. He was an enigma and I always had regard for his opinion.

“I listened to him and I learned from him,” Coley continued. “We didn’t always agree and it wasn’t always easy and it wasn’t always fun but it definitely was always entertaining for sure. Dan adored his older brother and it was because of Jimmy opening doors for us that we came to Los Angeles to record and meet the right people. … He belonged to a group that was one of a kind. I am very sad over this but I have some of the best memories of all of us together.”

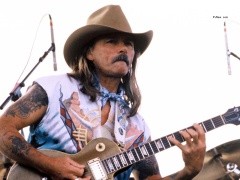

For several years in the late ’50s and early ’60s, both Seals and Dash Crofts — who survives his partner — were members of a group that bore little stylistic similarity to their later act: the Champs, although they joined after that band had recorded its signature hit, “Tequila.” Seals played sax in that group and Crofts was on drums.

James Eugene Seals was born in 1942 to an oilman, Wayland Seals, and his wife Cora. ““There were oil rigs as far as you could see,” Seals told an interviewer of his upbringing in Iraan, Texas. “And the stench was so bad you couldn’t breathe.” Jim became transfixed by a visiting fiddler and his father ordered him an instrument from the Sears catalog when he was 5 or 6. In a 1952 contest in west Texas, Jim won the fiddle division while his father triumphed in the guitar category. His little brother, Dan, later to be a pop star himself, took up the stand-up bass.

Jim took up sax at age 13 and began playing with a local band, the Crew Cats, when rock ‘n’ roll broke out in 1955. The shy musician joined up with the more outgoing Darrell “Dash” Crofts, who was two years older and grew up the son of a Texas cattle rancher, inviting his friend to join the Crew Cats as well. In 1958, the offer came to join the Champs, who’d recently had a No. 1 smash with “Tequila.” They stayed with that band till quitting in 1965.

The pair moved to L.A. and joined a group called the Dawnbreakers, also playing for a time behind Glen Campbell, just before he broke out as a major star. Their manager, Marcia Day, was a member of the Baha’i faith, and the house they shared on Sunset Blvd. was full of adherents as well as secular members of the local rock scene; in 1967, five years before having their first hit, both Seals and Crofts converted.

“She and her family were Bahai, and they’d have these fireside gatherings at their house on Friday night,” Seals recalled in a 1991 interview with the Los Angeles Times. “There were street people, doctors, university teachers and everybody there. And the things they talked about, I couldn’t even ask the question let alone give the answer: the difference between soul, mind and spirit, life after death. We’d discuss things sometimes until 3 in the morning.

“It was the only thing I’d heard that made sense to me, so I responded to it,” he continued. “That began to spawn some ideas to write songs that might help people to understand, or help ones who maybe couldn’t feel anything or were cynical or cold. Lyrically, I think music can convey things that are hard sometimes for people to say to each other. But through a song, through someone else’s eyes, they can see it and it’s not so much a confrontation.”

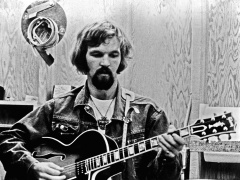

Abandoning their former instruments for something more folk-rock-friendly, Seals took up the guitar and Crofts learned the mandolin. Their first three albums as a duo, between 1969-71, had a sweet sound but went little-noticed. They tried cutting “Summer Breeze” earlier but didn’t come up with a version they liked until their third album in 1972, which they named after the track. It caught on at radio, region by region. Seals was quoted in Texas Monthly as having noted the sudden shift when they arrived for a gig in Ohio: “There were kids waiting for us at the airport. That night we had a record crowd, maybe 40,000 people. And I remember people throwing their hats and coats in the air as far as you could see, against the moon. Prettiest thing you’ve ever seen.”

After several more major and minor hits followed, including “Diamond Girl,” wrote Texas Monthly, the duo had their own private jet yet “would come out and sit at the edge of the stage and hold firesides about the Baha’i faith with curious fans. In 1974 they played the California jam, along with Deep Purple and the Eagles, in front of hundreds of thousands. When Jim pulled out his fiddle for a hoedown on ‘Fiddle in the Sky,’ throngs of sunbaked hippies clapped along.”

The duo stirred controversy in 1974 by recording an anti-abortion song, “Unborn Child,” as their album’s track in 1974 in the wake of the Roe v. Wade decision. The belief that abortion was wrong came out of their shared Baha’i beliefs, and they released it over the objections of their label, Warner Bros.

The divisive song “was really just asking a question: What about the child?” Seals told the L.A. Times years later. “We were trying to say, ‘This is an important issue,’ that life is precious and that we don’t know enough about these things yet to make a judgment. It was our ignorance that we didn’t know that kind of thing was seething and boiling as a social issue. On one hand we had people sending us thousands of roses, but on the other people were literally throwing rocks at us. If we’d known it was going to cause such disunity, we might have thought twice about doing it. At the time it overshadowed all the other things we were trying to say in our music.”

In 1977, the duo contributed to the soundtrack for a basketball-based film, “One on One,” starring Robbie Benson. They didn’t write the songs — Paul Williams and Charles Fox did — but were prominently billed on the soundtrack album as the song score’s performers.

By the time they broke up in 1980, their brand of music was finding far less of a place in disco-fied top 40 stations. Seals moved to Costa Rica with his wife, Ruby, where they were reported to have run a coffee farm as they raised their three children, and Crofts and his family moved to Mexico and eventually Australia.

In 1991, when Seals and Crofts made a stab at a reunion, they talked about their breakup with the L.A. Times. “Around 1980,” Seals told the newspaper, “we were still drawing 10,000 to 12,000 people at concerts. But we could see, with this change coming where everybody wanted dance music, that those days were numbered. We just decided that it was a good time, after a long run at it, to lie back and not totally commit ourselves to that kind of thing because we were like (fish) out of water.”

Seals, who later moved to Nashville, was considered to have been retired from a music career even before he suffered a stroke in 2017 that put a halt to his playing.

But he did occasionally return to music in the intervening years, as when he toured with his brother Dan (aka England Dan) as Seals and Seals.

The Seals name has a legacy in music that goes beyond just Jim’s, as multiple generations in the family tree have taken up performing or songwriting. Besides Dan’s tenure with England Dan and John Ford Coley and cousin Brady Seals’ success with Little Texas, another cousin, Troy Seals, is a Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame member responsible for such hits as “Seven Spanish Angels,” and in the ’50s his uncle Charles “Chuck” Seals co-wrote the Ray Price classic “Crazy Arms.”

Seals is survived by Ruby and by their children Joshua, Juliette and Sutherland.